Dr Ken McNamara, University of Cambridge was guest speaker for Armadale Branch meeting in April 2017.

Ken began his talk by stressing the importance of looking at the nature of rocks and fossil plants in helping to understand past climates. In particular they have helped show that over the last half a billion years, the Earth has experienced long periods of alternating ‘Greenhouse’ and ‘Icehouse’ worlds. During the former, CO2 levels and global temperature were much higher than in the current ‘Icehouse’ world we inhabit.

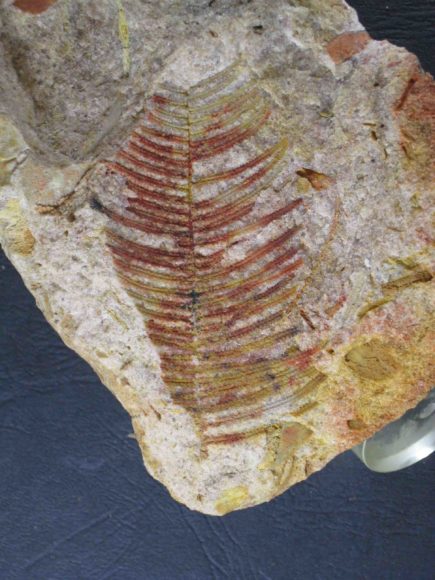

Ken’s talk centred on two fossil plant sites, both of which have only received preliminary studies. One, dated at about 130 million years old (Cretaceous Period) is near Kalbarri. The other, about 40 million years old, is at Walebing, east of Moora. They are very different from one another in that the older site near Kalbarri contains plants living before the advent of flowering plants. The fossils show that the area was dominated by ferns (about 40% of the flora), including gleicheniacean, dipteridacean and osmundacean types. The rest of the flora was mainly arauraciacean conifers (25%) and an extinct group, the seed ferns (25%). The rest are forms yet to be identified. Some of the seed ferns are similar to fossils found in India, which was close to Australia at this time. While much of the fossil plant material is leaves and broken branches, there are a number of seeds and also frequent seed scales from the conifers.

Like this Cretaceous flora, the younger 40 million-year-old (Eocene Epoch) Walebing site preserves the fossils as impressions in very silicified sandstones. These rocks are known as silcretes and reflect formation at a time when the climate was much wetter and warmer than today, despite being located at much higher latitudes than now (55°–60°), with pronounced seasonality. The fossils are very common and reflect a very diverse flora, dominated by proteaceans, such as banksia, grevillea and possibly macadamia. The very diverse array of banksia leaf types show biodiversity levels were high even at this time, and probably had been on the nutrient-poor soils for tens of millions of years before, back into late Cretaceous times.

As well as these sclerophyllous plants the flora also contains rainforest elements, such as the Southern Antarctic beech, Nothofagus and many myrtaceous leaves that resemble modern rainforest types. Araucareaceans are still present, as well as casuarina-type fruiting bodies, including some types present today only in rainforests in eastern Australia and New Caledonia.

Study of the leaves of one of the banksia species, B. paleocrypta, shows that it has sunken stomata, suggesting that it was preadapted for the drying out of the Australian continent that has occurred over the last 25 million years or so. The rainforest elements have disappeared from WA, leaving only those forms, such as the proteaceans, that were preadapted to both the nutrient-deficient soils and the seasonal periods of low water availability.

In his closing comments, Ken pointed out that much more work needs to carried out on these floras. This will help provide a better understanding of the evolution of the rich flora that we see in Western Australia today.