Smaller Eucalypts & Taller Eucalypts for Planting in Australia

Eucalyptus is an important genus of the world’s plants. It is significant that Australia is the only continent in the world whose vegetation is dominated by a single genus of plants, namely Eucalyptus. In addition, this particular genus is almost unique to our continent (with just a few species occurring on islands to its north, including New Guinea). Some species grow almost to the tops of our tallest snow-capped mountains, others down to the surrounding seas, and others again, from the edges of rain forest to the depths of our deserts. They are THE outstanding living feature in most natural Australian

landscapes and the key element that impart identity to an Australian scene.

Yet the majority of us don’t know the names (i.e. the botanical identity) of more than a few. The prime reason being that Eucalyptus is a large, diverse and complex genus, with widely scattered species, some growing in as yet seldom visited locations and undoubtedly with a number as yet to be discovered. It has been difficult for botanists to comprehend the whole assembly; and quite a number of species have until recently not had their botanical names determined. Into the bargain, even when named, it hasn’t been easy for an average person to work out what name applies to ‘their particular plant of interest’. And it is a fact that when an object doesn’t have an identity, it is almost impossible to advance your interest and knowledge pertaining to it, apart from what you observe at the time. Even if you are initially strongly motivated, and desperately wanting to further your quest, there is sadly no meaningful mechanism for storing/recalling information so that it relates to an unnamed object, i.e. until it has a name, there is nothing to attach information to. This situation has been an impediment from the beginning of the landscape development of our settlements in this continent. It is a pivotal factor that has detracted from the use, as well as the recognition, acknowledgement and understanding of the value and importance of this unique and inestimable natural asset, ‘our Gum Trees’.

It is thus not surprising, that as a consequence, up until now, eucalypts have sat in both the amateur’s and the professional botanist’s ‘too hard basket’, with only the occasional ‘tackling by taxonomists of a few species,’ or ‘of a segment of this genus’. We have thus had to wait for a very long time for this large group of our Australian plants to be recently taxonomically unravelled as a whole, and for many of the individual species to be named. Eucalypts (our widespread, ‘national tree’) have suffered a great disadvantage as the result of this situation. To a large degree they have been neglected, underestimated and often even ignored; as without a name, it is impossible to assemble, transmit or retain pertinent retrievable information related to a particular species or even to individual trees.

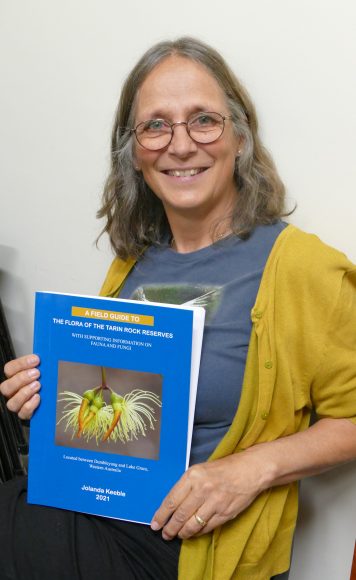

Dean Nicolle has now completely changed this situation for us. It is a joy and a revelation, to at last have to hand, such a lucid and pertinent pair of books on the “Gum Trees” that we grow and also on others that we would want to grow now that we have more information about them, and can find out what their names are. Due to his diligent research, and now with the publication of this beautifully illustrated pair of companion volumes, he has provided us all with a readily accessible means of identifying the gum trees we grow. A facility that we, as members of the Australian public, have needed and

been seeking, ever since we first began to take notice of the trees that are growing around us. With the assistance of these manuals we will now, at long last, be enabled to determine their correct botanical names, and to record and consult data about them.

His information for each species is written in simple English, lucid and to the point. The plant’s botanical name is followed by its common name, (if it has one). Then the origin of these names and what they mean or refer to. Next comes a clear, concise description, covering pertinent points and distinctive features. Then successively: Natural distribution & habitat; Cultivation & uses; and Management, followed by notes on Similar species (these are most helpful in making a diagnosis). This text is accompanied by clear, informative photographs that illustrate the pertinent features that immediately help to

identify the plant of interest; a chart of the plant’s (cultivation) Preferences and a map of its natural distribution.

The major additional benefit from this publication is the fact that once a plant has a botanical name, information about that plant such as special attributes, capabilities and potential under a variety of conditions, will accumulate. This species information will be of help in future choices made for planting in specific situations.

This is a treatise that was well worth waiting for and will prove to be the tool to familiarise us all with a most interesting selection of our nationally dominant genus of plants.

So, all you Wildflower People, the field is now open to find out what you’d like to grow that fits your particular situation. Go to it. Dean Nicolle has opened the door for us to embrace and begin to understand what is probably our most significant living National Asset.

-Marion Blackwell, convenor of the Society Publications Committee